Why Do So Few Nigerians Have Health Insurance?

I wasn’t a particularly sickly child growing up in Nigeria. If I had a headache, my parents would give me paracetamol. If I came down with malaria, I was administered chloroquine (which caused my body to itch), and later, Fansidar or some artemisinin-based medication. All these drugs were reasonably cheap, paid for out-of-pocket, and generally effective. Within a few days of completing treatment, I was often back on my feet.

My earliest memory of being admitted to a hospital was due to food poisoning after I insisted my parents get me pizza. This was back in the mid-1990s, and food hygiene standards were not what they are now in places like Galaxy, Dominos, and other big chain pizzerias in Nigeria today. I probably voided a good proportion of my weight through both ends of my alimentary canal - but I was fortunate to be discharged the same day.

Another time, I had been playing basketball outdoors in high school and drank water from a nearby tap. I didn’t think too much about it because I had not seen my peers suffer any damage after drinking from the same source throughout the school year. Later that same day, I came down with a severe case of typhoid fever and had to be admitted to the hospital. I wasn’t discharged for another 2 - 3 weeks. Needless to say, I missed a good chunk of what was left of the school term and barely made it back in time for the final exams.

We didn’t have health insurance and my parents had to pay my hospital bills during these episodes out-of-pocket. Looking back, I am grateful they were able to do so. We were on the lower end of the middle class, but we had a safety net made up of extended family members and friends we could reach out to if push came to shove.

Not everyone has that option. Many Nigerians often face a ‘double whammy’ where they are vulnerable to many preventable diseases while also lacking the financial capacity to pay for healthcare. Even more puzzling is the fact that, although Nigeria has been operating a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) since 2005, less than 5% of the population is formally enrolled in health insurance.

So, what’s going on? Why is health insurance coverage so low in a country with an existing health insurance framework and widespread vulnerability to preventable illnesses?

How to Study Demand Without Selling Insurance

Measuring demand for health insurance in a society where the bulk of the population is uninsured can be tricky. Large-scale studies are possible, but can be slow, expensive, and logistically complicated to pull off.

At PROMISE Labs Africa, we approached this problem from a different angle. We designed a short survey presenting 15 different monthly insurance price points ranging from ₦5 (less than $0.01) to ₦560,000 (a little more than $370). For each price, we asked our Nigerian respondents whether or not they would be willing to purchase insurance coverage for themselves.

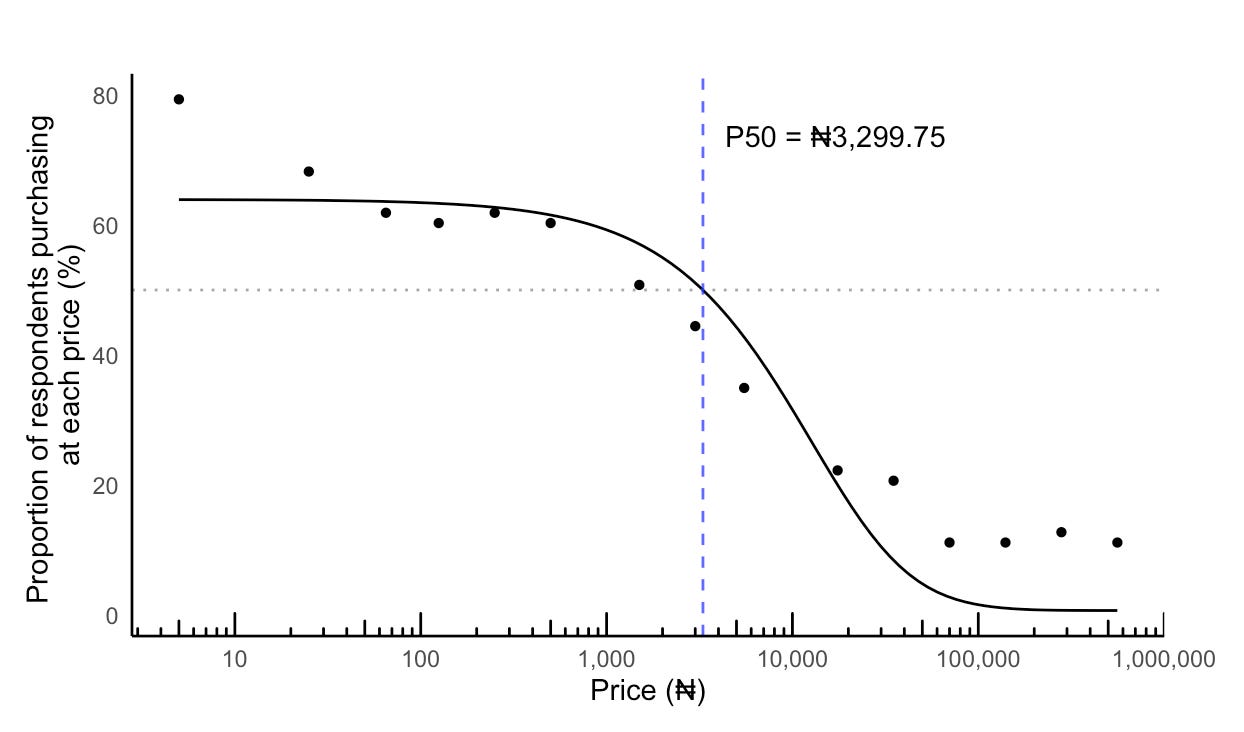

This is what we found after aggregating the responses we got from 63 Nigerians who completed our survey:

As you can see, it follows what you’d expect. At lower prices, most participants say ‘Yes’ , and as the price increases, more participants start to say ‘No’. While the overall downward slope is intuitive, let’s focus on that price point where 50% of the respondents say ‘Yes’ and the remaining say ‘No’. We will call this the P50.

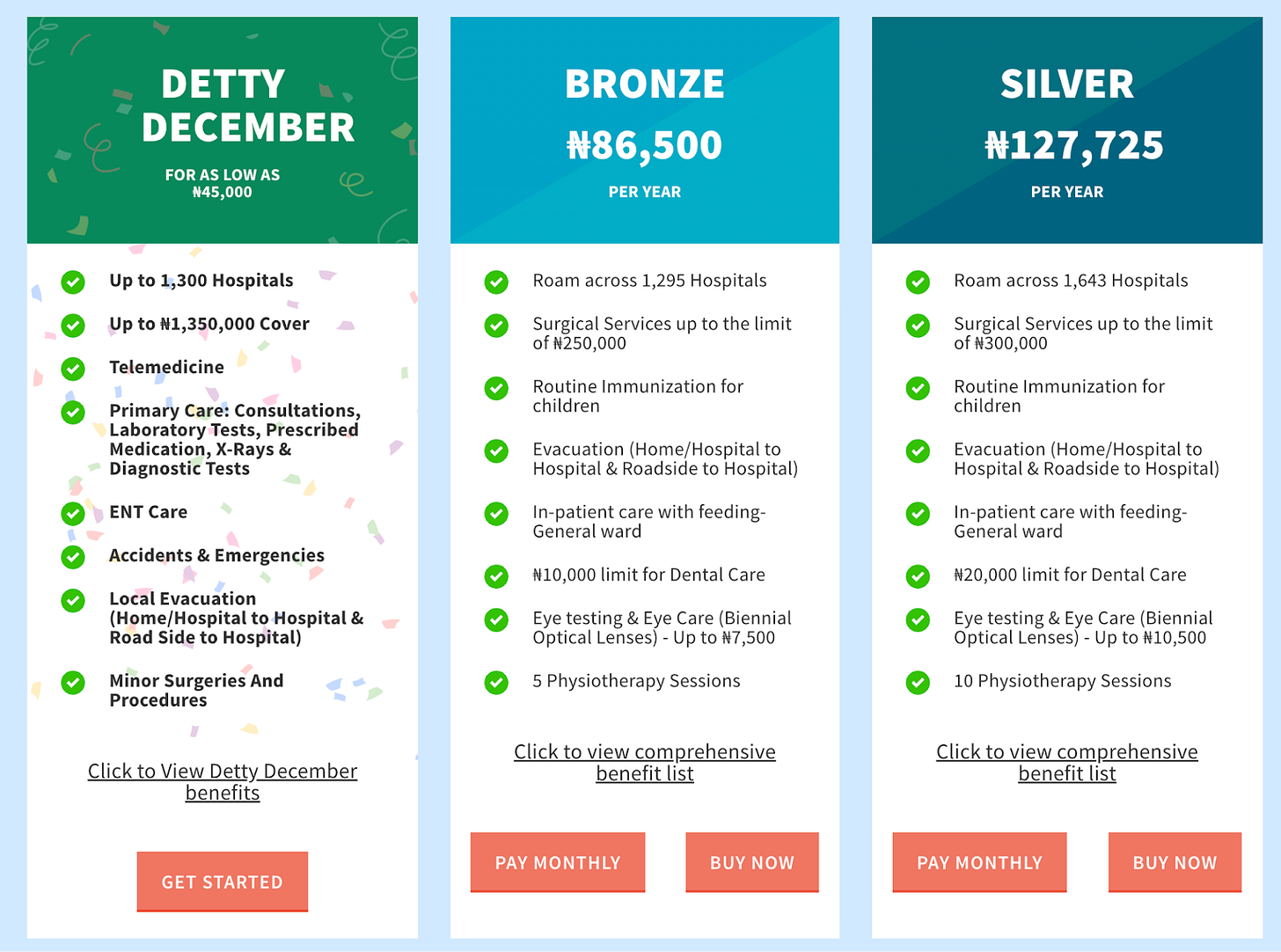

For this sample, P50 was ₦3,299.75 (≈ $2.20), which translates to roughly ₦39,600 per year (≈$26.40/year). For comparison, Figure 2 shows the three lowest yearly plans on a private Nigerian insurance platform, AXA Mansard, gradually gaining popularity.

Who Can Afford What?

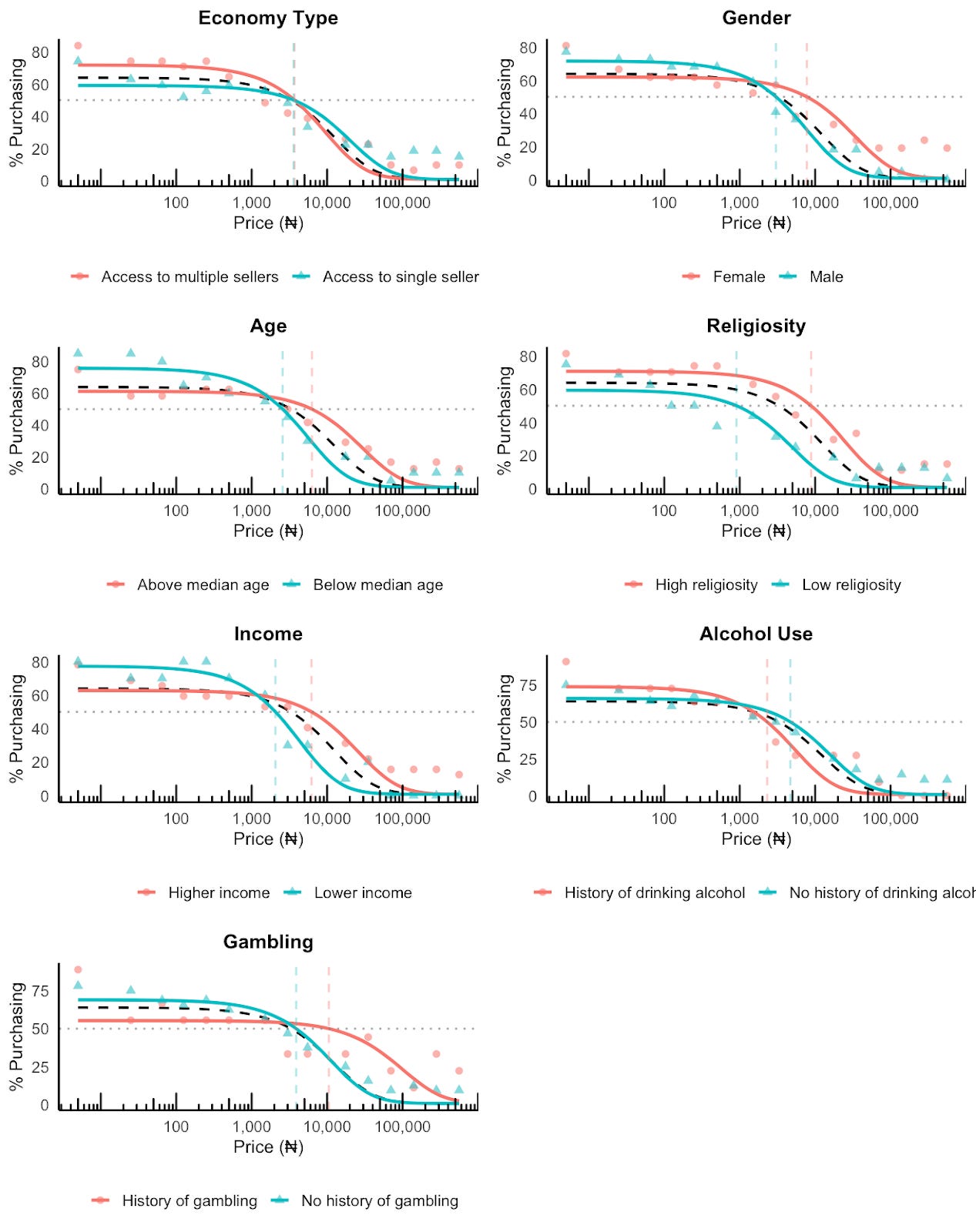

Merely looking at the overall curve in Figure 1 hides a lot of things. When we broke down the aggregate data by the different demographic groups, the P50 values shifted around in really interesting ways.

Here’s what we found out:

Income: As expected, higher-income respondents had a P50 (₦6,201.31; ≈$4.13) roughly three times that of lower-income respondents (₦2.062.11; ≈$1.37). That said, at very low prices, a higher proportion of lower income earners responded ‘Yes’ compared to higher income earners.

Age: The P50 for older people (₦6,279.21; ≈$4.20) was more than 2 times that of younger people (₦2,571.22; ≈$1.72). This makes sense as older people tend to be more established in their careers and are typically higher income earners than younger people. Older folks are also likely to face more health challenges compared to younger people and may consequently value health insurance more.

Gender: Women exhibited a P50 of ₦7,750.12 (≈$5.17), more than 2.5 times that of men at ₦3,021.95 (≈$2.00). This likely reflects women’s roles as the primary health decision-makers in their households. That said, we found a higher proportion of men saying ‘Yes’ to health insurance at very low prices compared to women.

Religiosity: Surprisingly, highly religious participants showed a P50 (₦8,829.97; ≈$5.89) that was nearly 10 times that of the less religious (₦905.75; ≈$0.60). You would expect highly religious individuals to value health insurance less because of beliefs in supernatural health and a perceived immunity from sickness. It is also possible that the highly religious respondents also happened to be high income individuals who could afford health insurance.

Alcohol consumption: Non-drinkers exhibited higher P50 values (₦4.686.89; ≈$3.12) than drinkers (₦2,309.02; ≈$1.54). It is plausible that non-drinkers simply have higher income levels than the drinkers and could therefore afford to pay more for insurance.

Gambling: The P50 for those with a gambling history (₦10,524.20; ≈$7.02) was almost 3 times that of non-gamblers (₦3,884.17; ≈$2.59). One explanation could be that gambling is associated with health issues and gamblers may see their premium as a license to engage in risky behavior (moral hazard). That said, at lower prices, the proportion of non-gamblers who responded ‘Yes’ was higher than that of gamblers.

Economy Type: Finally, whether respondents were told they could purchase insurance from multiple sellers (₦3694.87; ≈$2.46) or only one (₦3591.48; ≈$2.39) had very little effect on P50.

What’s Happening Under the Hood?

We knew that demand would vary with the characteristics of the different participants in our sample. However, we wanted to find out if there were other factors at play that we hadn’t considered in our survey.

To get to the root of this, we asked those who had completed our survey if they were interested in being interviewed. Fortunately, we had five people who indicated interest and showed up in a focus group style interview. Because a couple of weeks had passed since the initial study, our team had these five participants take the same short survey again before we started asking them to share the rationale behind their choices.

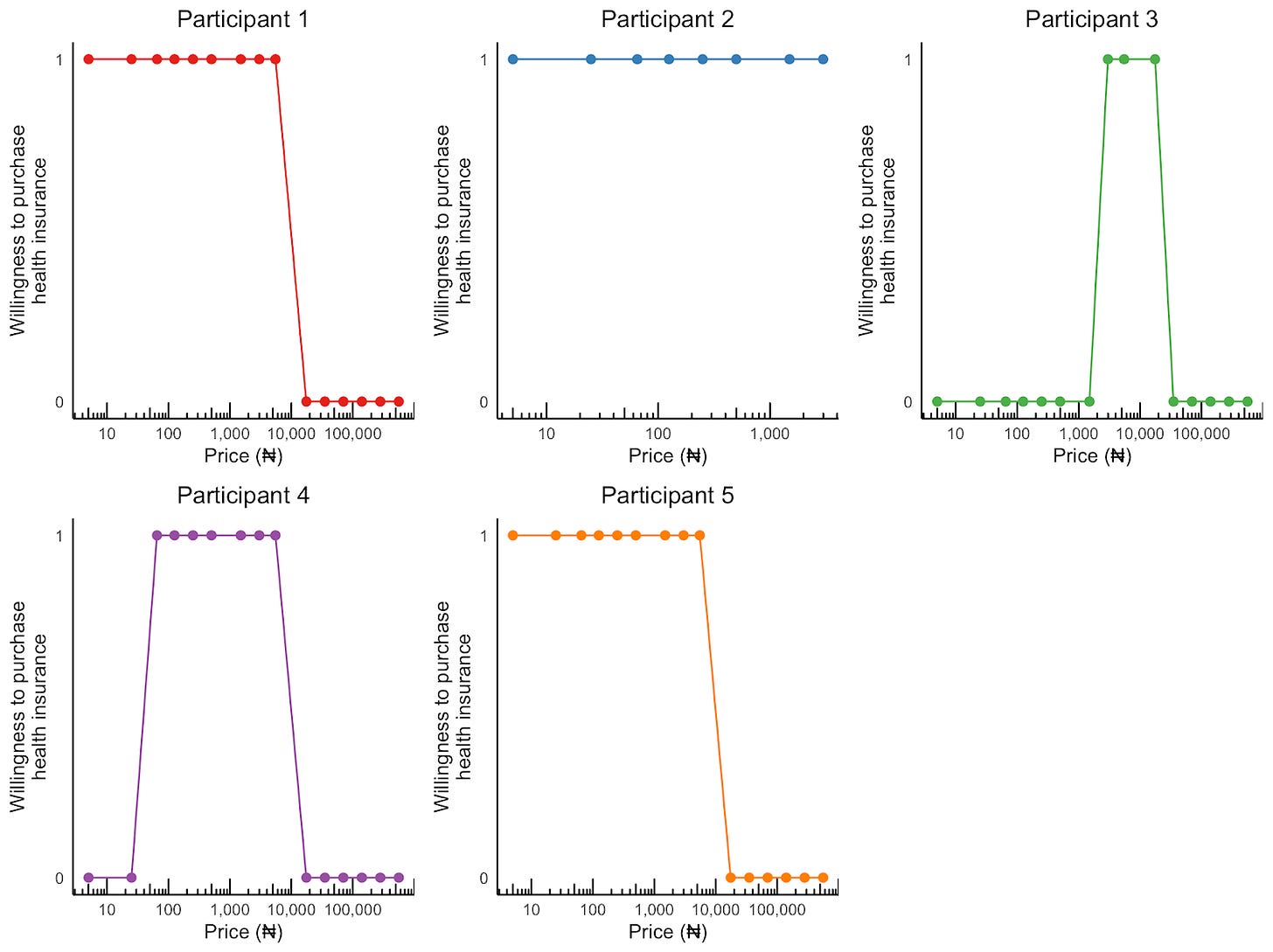

Before we go over their responses, the figure below shows the response pattern of the 5 participants we interviewed.

As you can see, Participant 1 and 5 had demand curves similar to what we had at the aggregate level. That is, when the price of health insurance was low, there was a strong willingness to purchase it. And after a certain threshold price was crossed (₦5,500/≈$3.67 for Participant 1 and ₦17500/≈$11.67 for Particpant 5), demand dropped to zero.

But there was something else going on, which would have been missed if you’re only looking at the data in aggregated form.

No, not Participant 2. She was willing to purchase health insurance at all prices up to ₦3,000 (≈$2.00) after which she just stopped responding. But take a look at Participant 3 and Participant 4. They both had a demand curve that took the shape of an inverted-U. In other words, they were unwilling to pay for health insurance if it was either too cheap or too expensive.

When we asked why they responded in this manner, Participant 3 said, “I chose “No”, from ₦5 to ₦1500, because I tried to live in the reality of things within the country. Basically, I tried to be realistic, and I know that [₦5 to ₦1500] is quite low for the situation.”

In the same vein, Participant 4 said: “I actually did not want to pick those ones [in] smaller currencies, because I felt...the quality of health care that I would be getting with that amount will not be so great... I’ll still prefer to pay a reasonable amount of money, even if it’s subsidized, so that I can be sure that I’m not getting Paracetamol or Vitamin C. I am sure that this is quality health care, not just a “figurehead” kind of insurance.”

In other words, a low-priced insurance coverage signals low quality to some Nigerians.

Additional factors that emerged as influencing how Nigerians valued health insurance include:

Family coverage: Participants deemed family coverage as higher in value to individual coverage. As one participant said: “If [the health insurance coverage] is going to involve my family, my husband, children, yes, [I will pay more]”

Perceived immunity: Some participants perceived themselves as relatively immune to serious illnesses and relied on pharmacists for routine care. One said: “If I feel a little bit ‘off’...well, to God’s praise, I rarely fall sick. But if I do, in those rare cases, I just go to the pharmacist and they prescribe something for me. I use it, and I’m fine.” This finding might be surprising to readers in developed economies where patients need a valid prescription from a doctor to access medication that cannot be obtained over-the-counter. In Nigeria, pharmacists do not have the legal authority to prescribe, although things are quite different in practice and many pharmacists dispense medication without a doctor’s prescription

Type of health facility covered: The value of an insurance plan is tied to the facility it covers. If the plan only provides access to Nigerian public/tertiary hospitals, notorious for their long wait times, the insurance loses its appeal. A participant noted: “I think the benefit [of health insurance] depends on which hospital you are registered with. If it is a public hospital or a tertiary hospital, the length of hours you have to stay on the queue before a doctor attends to you can be disheartening.”

Distrust of Nigerian institutions: A broader skepticism towards the Nigerian political class and the institutions they lead shapes how government-led insurance initiatives is valued: “It’s difficult to say some things in Nigeria because of the way the political leaders take decisions...I think there is already…an institution in charge of [health insurance]. That’s the NHIS. It’s good that people will get access to health care easily and at a cheaper cost, but in the long run, because of the way the country is, it could just get corrupted and become something that is not worth it after all.” This attitude might partly explain the low enrollment rates in the NHIS.

Policy Implications

Although our sample size was small, the findings from this study highlight a number of considerations for policymakers and private insurers serious about increasing enrollment rates in Nigeria.

First, a single-minded focus on making health insurance as cheap as possible may not have the intended results. Yes, certain subgroups showed a greater willingness to buy insurance at low prices (e.g., low-income earners, young people, and men). But at the same time, we found that extremely low prices may also be interpreted as a pointer to inferior services. For a country trying to increase enrollment rates, the last thing it wants to do is to antagonize women, who are often the main health decisionmakers in their households. Where insurance costs can be legitimately reduced without diluting the benefits, marketing efforts must focus on communicating this clearly so that people don’t automatically associate cheap with inferior.

Second, there needs to be tiered plans for population subgroups who demonstrate high demand at extremely low prices. There’s clearly an underserved market here. But these subgroups need more than just subsidized fees; they also need their benefit packages customized to their financial realities (e.g., unstable income, irregular employment) and their vulnerabilities (e.g., infectious disease treatment, basic maternal health care).

Third, we observed that there was a higher demand for health insurance among the more religious respondents, though this could have been because the high income respondents in our sample also happen to be very religious. Regardless, religious communities and institutions can be a potentially powerful ally that policymakers and private insurers are currently overlooking in their efforts to increase awareness and ultimately enrollment across the country.

Fourth, the workings of the insurance process needs to be made as intuitive and transparent as possible. As our interviews revealed, Nigerians are already quite distrusting of government institutions and initiatives. Therefore, any efforts made towards simplifying the enrollment process, clarifying what is and is not covered, and making the claims process as straightforward as possible will go a long way in reducing skepticism about insurance actually delivering when needed.

Finally, more work needs to be done in improving patients’ experience in public and tertiary hospitals. The recurring refrain of long queues and poor services need to be a thing of the past. Investments in staffing, infrastructure, professionalism, and reduced wait times would go a long way in increasing the perceived value of health insurance, and ultimately, enrollment rates.

Many thanks to Emily Brooke Felt, Dolores Lucero, and Ved Shankar for the conversations and feedback that shaped this essay.

Great original research. I can't comment on the methodology, but I appreciate reading about it.

Curious about the P50 for women - do you think women being key financial decision-makers is the most salient factor, or is there perhaps a health-oriented mindset too (women are something like 2x more likely to have autoimmune problems compared to men, a chromosomal effect from the double XX).