The Behavioral Science Revolution Africa Needs

How Microgrants and Local Leadership Can Reshape the Continent from Within

I.

About ten years ago, I found myself in Twon-Brass1, an island tucked into the oil-rich belly of Nigeria’s Niger Delta. It sounds a bit glamorous until you are actually there. I was doing community fieldwork for an HIV/AIDS program: walking under the scorching sun, soaked in sweat, doing my best to convince poor, skeptical fishermen to take an HIV test.

After a day’s work engaging with the locals, my colleagues suggested we check out the island’s beach.

It was breathtaking.

Untamed. Unfiltered. Just sand melting into the sea, shrubs swaying lazily, and a sunset so cinematic it would make a poet out of anybody. The air tasted of salt and possibility.

But something was off. Where are all the people? The beach bars? The hotels? The tourist traps selling overpriced coconut drinks? The fancy homes with straw hats hanging on doors?

This place should have been a weekend getaway destination buzzing with life. Instead, it was just nature doing its thing, quietly. And my colleagues and I, standing there with our jaws unhinged.

But then, things got stranger: just a few minutes’ walk inland from the beach, stood concrete fortresses of multinational oil companies. It looked as if someone had changed the channel on reality. Their fences soared high, crowned with enough barbed wire and paranoia to make you wonder if they were keeping something in or something out. Some buzzed with electricity, in case the barbed wires weren’t clear enough.

As I walked through the island, caught halfway between paradise and power, I couldn’t help but wonder:

How can a region literally floating on billions of dollars’ worth of crude oil2 leave its people with so little to show for it?

This wasn’t just a Twon-Brass thing. Similar contradictions play out all over Africa. We’ve got the natural resources, oceans of foreign aid, the programs, the slogans…and still, Africa continues to wallow beneath its potential. This gap continues to puzzle researchers and policymakers alike.

The usual suspects get paraded whenever this topic comes up: widespread corruption3 4 (check), weak institutions5 6 (check) and poor governance7 (triple check).

Yet, I believe that the root cause is something much more fundamental: Too often, the behavioral insights informing initiatives and interventions implemented in Africa come from studies done in Western societies - on people who look, think and live nothing like Africans! The result? Fancy initiatives with glossy logos that don’t stick because they were never rooted in the local soil in the first place.

For Africa to truly thrive, we need behavioral research led by Africans, shaped by African realities, and agile enough to respond to the pulse of on-the-ground dynamics. It is only when we truly understand the African decision-making landscape that we can design initiatives, interventions and policies that don’t just look good in PowerPoint slides but actually work in the villages, towns, and cities where real Africans live their beautifully complicated lives.

II.

Decision-making anywhere is messy. It’s often not as straightforward as weighing your options, picking the rational8 one, and boom - problem solved, satisfaction maximized! This is even more so in the African context.

When an African falls sick, for instance, the decision tree doesn’t simply branch to “Go to the hospital” or “Take medication”. There may also be “Could this be a spiritual attack from that lady who gave me a side-eye at a wedding three years ago?” and “Is this a generational curse because my great-great-grandfather allegedly stole a goat in 1823?” And even if you do make it to the clinic, an auntie three states away may still insist you also need to see a prophet or spiritualist just in case.

Similarly, in daily interactions, decisions often hinge on how well you can read between the lines, not just on what people are actually saying. And getting this wrong can lead to wildly different outcomes. A smiling “It’s fine” from an offended party could mean anything from “It’s genuinely okay” to “I will remember this betrayal until my dying day.” Whether you drop the topic or launch into damage control mode depends entirely on which one it actually is. “I’m on my way” can mean anything from “I'll be there in five minutes” to “I might arrive next Thursday, weather permitting.” That’s why anyone who has organized events in Africa has learned to put “NO AFRICAN TIME!” on invitations - because without it, a 5 pm start time might be interpreted as “5 pm is when you should start getting dressed.”

The same thing plays out in money matters. You land a job, and you think, finally, I can save, update my investment portfolio, and build a life. Not so fast - you’ve got dues to pay. Not taxes in the IRS sense, but something heavier. We Africans call it “Black tax”9: an unwritten social contract where your success belongs to everyone who shares even a drop of your DNA. Whatever individual achievements you have automatically becomes collective property - there’s no opting out, no negotiating the terms. Your cousin needs school fees? That’s on you. Uncle’s roof is leaking? Open your wallet. The neighbor who helped raise you needs capital for their business idea involving imported Brazilian hair? Congrats, you’re now a venture capitalist!

Even the “educated elite” aren’t immune to these dynamics. During my undergraduate days at the University of Ibadan (Nigeria’s first and finest!), I occasionally stumbled upon what can only be described as ritual sacrifices left on campus grounds. I’m talking about palm oil, kola nuts, moin-moin10, and eko11, wrapped in uma12 leaves and arranged in a calabash13. Were they placed there by a student desperately trying to pass CHEM 157, or a lecturer trying to get tenure? I didn’t dig around to find out. But the fact that someone thought that appeasing ancestral spirits was a reasonable strategy within the four walls of a university powerfully illustrates just how context shapes behavior.

The anthropologist Joseph Henrich14 probably wasn’t thinking specifically about my calabash encounters when he wrote his 2020 book “The WEIRDest People in the World”. In the book, Henrich compellingly argued how Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) populations demonstrate psychological characteristics that are extreme compared to the global average. WEIRD societies favor individualism over community (no “Black tax”), think analytically instead of holistically (see success and health as independent of spiritual forces), prefer direct, explicit communication over subtext (5 pm is 5 pm), and trust strangers sometimes more than family (no fears of spiritual attacks from a side eye at a wedding)!

Yet, almost everything we think we know15 about human behavior comes from studying this small slice of humanity. It’s like trying to understand fruits by exclusively studying oranges.

The same thing happens when you try to apply WEIRD science to non-WEIRD realities.

You get fancy theories that don’t land; policies that misunderstand people; and behavior change campaigns that don’t work. The PMTCT16 programs that banned traditional birth attendants (TBAs) from deliveries17 to prevent HIV transmission are a case in point. These programs dismissed these TBAs, despite them being the most trusted healthcare providers in their communities. This led to many women opting out of facility-based births altogether, ultimately missing out on the very life-saving interventions the programs were designed to deliver.18

III.

Let’s be clear: you cannot outsource an Afrocentric behavioral science. You may ship in consultants, fly in PhDs, import theories with footnotes longer than an adult’s arm - but if the people collecting and interpreting the data don’t live the realities on the ground, something vital gets lost in translation. It’s like asking someone who has never tasted jollof rice19 to judge a West African cooking contest. They might be a Michelin Starred chef, but they are still missing that essential something - the lived experience that tells you when the spice balance hits that sweet spot between “delicious” and “my mouth is on fire!”

Centering African researchers at the forefront is not about ticking the diversity checkboxes on grant applications or adding “local ownership” buzzwords to donor reports. It is a matter of pure pragmatism!20

African researchers have the ultimate home-field advantage. They live in the communities they study. They ride the okadas21 through the dusty backroads, and understand why someone who might ignore a public health directive from the government will listen to warnings from their grandmother’s dream. They catch the unspoken meanings, the subtle head nods, the pregnant pauses that communicate volumes. These are the people best positioned to ask the right questions and make sense of the answers.

They also have what Nassim Nicholas Taleb22 calls “skin in the game”. This means that, unlike foreigners who can just pack their bags and head back to Geneva or D.C. when things go sideways, African researchers must live with the consequences of the policies and interventions their work informs. So, when an African researcher analyzes how political decisions affect behavior, it’s not some abstract problem on a spreadsheet - they are actually watching how those policies ripple through their neighborhoods, families, and WhatsApp groups. When your own mother might use the healthcare system you’re analyzing, you are no longer just doing research to get tenure - it becomes personal. There is no evacuation operation. There is no Plan B. This creates a built-in accountability mechanism that no ethics committee could ever replicate.

IV.

So, if African researchers are so well-positioned to lead behavioral research on the continent, why aren’t they doing more of it?

To be fair, some are. The Busara Center23 in Kenya, for instance, is doing world-class, African-led behavioral research, and there are other promising initiatives across the continent. But the reality is that these are still exceptions rather than the rule.

Behavioral science in Africa is full of really smart people. But many of their ideas are scribbled in notebooks, whispered over campus benches, or filed away in laptops with cracked screens - not because they aren’t good, but because the researchers don’t have funds.

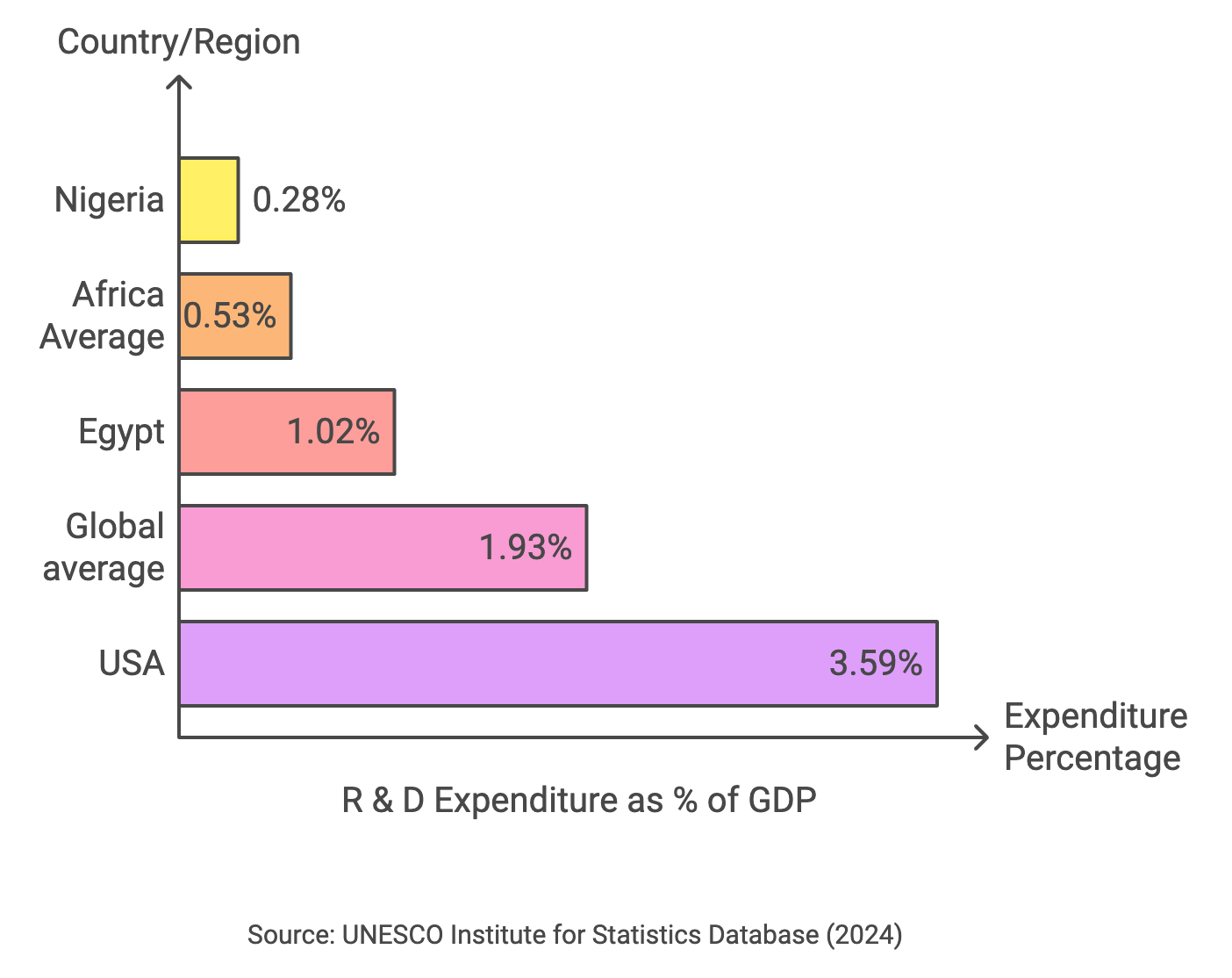

African governments often talk a big game about supporting research, but their wallets tell a different story. Back in 2006, the African Union members made a solemn promise to spend at least 1% of their GDP on research and development.24 Fast forward to 2024, and exactly ONE country - Egypt25 - has kept that promise. That’s it. One country out of fifty-four. The rest? Most are limping along at 0.5% or less26, and behavioral science is lucky if it even gets a slice of that tiny pie.

Why? The reasons are many. Low tax revenues.27 Resources diverted to foreign debt repayment and other competing priorities.28 And then, there’s the steady brain drain of African talent.29 But there is another reason that rarely makes it into the policy briefs: research just isn’t shiny.

African politicians love things they can cut ribbons on. Roads. Boreholes. Public toilets.30 Bags of rice handed out with a smile and a selfie during election season. Behavioral research? Nope. Too slow. Too abstract. It doesn’t make the headlines. It asks uncomfortable questions, and it’s harder to stamp your face on it for campaign posters.

So, instead, foreign institutions swoop in with their checkbooks and slick PowerPoint decks. Foundations, multilaterals, global consultancies. The nonprofit industrial complex - they are the ones bankrolling research on the continent. But here’s the issue: they often come with their own agendas and priorities. They arrive with pre-packaged research questions, methodologies, and expected outcomes that often have little to do with local realities. It’s like someone planning your weekly meals without asking you what you actually like to eat.

These organizations operate on funding models that prioritize neat numbers and photogenic success stories with tidy endings.31 32African researchers who want funding from these sources have to play by their rules and are often reduced to local implementers of someone else’s vision. That’s what happened in 2021 when the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative awarded a $30 million grant to institutions in America, U.K., and Australia to combat a disease that primarily affects Africa. Not a single African research institution made the list!33

Even when funding does get approved, a good chunk of it gets eaten up by “administrative overhead”. Translation: money for office chairs in New York and compliance meetings in London. By the time funding trickles down to actual researchers on the ground, it’s a fraction of what was pledged - and even that comes with strings attached.

Under these conditions, success gets redefined. It’s no longer about creating lasting positive change but about keeping donors happy with glossy reports and superficially impressive metrics. When success is measured by scale and speed, “We distributed 1,000,000 mosquito nets in the first quarter of the year!” can sound more impressive in a donor report than “We spent one year trying to understand why families keep using the mosquito nets to fish”34 35The unspoken goal shifts from solving Africa’s problems to managing them just well enough to justify the next round of funding. Running just enough programs to say “something is being done,” but not so much that anyone actually has to change the system.

V.

What if we didn’t wait for institutions with giant wallets and slow clocks? What if the part of answer wasn’t more money - but different money?

There’s a potential game-changer hiding in plain sight: microgrants from individual donors.

I’m talking about modest sums - $100 to $1,000 - that might seem insignificant in the grand scheme of international development but can spark revolutionary research when placed directly in the hands of African researchers.

Some people roll their eyes at the word “micro”. I know. It sounds…small. Cute even. Like five pieces of cashew nut when you were promised a feast. But in the right hands, a microgrant is rocket fuel. Think of microgrants as behavioral science's version of guerrilla warfare36 - nimble, adaptable, and surprisingly effective.

Now, to be clear, no collection of microgrants would ever be enough to build research labs or fund large-scale, ten-year studies tracking behavioral changes across entire populations. And that’s exactly the point! The goal here is not to give up on the fight for serious investments from major funders and African governments. Rather, it’s to make sure we’re not sitting around twiddling our thumbs while waiting for systemic change. With microgrants, African researchers can gather early data, build momentum, and create a pipeline of African-led research.

Conventional grants, for their part, often involve forms, committees, bank letters, institutional sign-offs, and what feels like a 12-step program to prove you’re not laundering funds through a ghost NGO. Microgrants? They can be awarded in days or weeks with minimal paperwork. This speed matters enormously in the rapidly evolving African context. For instance, suppose a new government rolls out a surprise policy (as they often do37), causing immediate behavioral ripples through communities. A researcher with a microgrant can pivot immediately to study these effects in real-time. Their traditionally funded colleague? Still updating their grant proposal’s timeline and getting signatures from thirteen different department heads.

Microgrants also create space for innovation and creativity. Because they are relatively small and low-stakes, African researchers can test unconventional research ideas that might sound strange in a formal proposal but could still lead to breakthrough insights. A researcher wants to study how African proverbs influence economic decision-making? Or how gossip shapes voter behavior? With microgrants, there is a chance to engage in this kind of ‘productive weirdness’.38 If it works? Brilliant - you’ve got proof of concept. If it flops? No big deal - fail fast, learn something, and try again.

This kind of freedom is rare in the traditional funding world, where risk aversion reigns and “innovation” often means “we added a dashboard that nobody asked for and nobody will use”. But for African behavioral researchers, especially early-career ones, microgrants are a license to tinker, explore, and get their hands dirty in the real world.

Perhaps the most magical thing about microgrants is their outsized impact. In many parts of Africa, where costs are relatively lower, $100 isn’t just spare change - it’s research transport, survey printing, airtime for Zoom interviews, maybe even a month’s rent for a grad student racing towards a deadline. With the current exchange rates, a single U.S. dollar can stretch farther than you’d expect. As of July 2025, for instance, one dollar gets you about ₦1500 in Nigeria - that’s enough for a research participant to catch a keke39 ride across town to take part in a focus group, and maybe still still leave them with change to grab a plate of iyán40 at a local buka41 if they know where to go.

That’s economic alchemy!

And the best part? Donors don’t have to be billionaires.

You. Me. Your group chat. Anyone with a little spare cash and a big belief in African research talent can fund this movement. Ten people chipping in $50 each could cover a full research project. A few hundred dollars could mean the difference between a brilliant idea dying in a notebook and generating insights that have the potential to challenge assumptions, spark conversations and ultimately inform real change in the community.

VI.

Let’s say you’re in. You believe in the power of microgrants. You’ve got a little money, a big heart, and maybe an itch to finally put some of your resources into something that isn’t an app designed in Silicon Valley.

Now what?

Here’s two ways to take action - depending on how deep you want to dive:

Option 1a: Fund our microgrant experiment.

I’m launching a pilot microgrant program through PROMISE Labs Africa42, the scientific nonprofit I run. When you contribute to our microgrant pool, your donation goes straight to individual researchers on the continent asking the questions that actually matter in their communities. No red tape. No overhead. No long delays.

If you’d like to help make that happen, you can donate here: https://givebutter.com/BMp3AA.

Whether you throw in $50 or $500, you’re helping spark the kind of research this essay has been arguing for all along: fast, flexible, locally relevant, and led by the people who live the questions.

As the program grows, we’ll share findings and insights from the researchers we fund: grad students, early-career scholars, and independent investigators across the continent. Over time, this will become a growing body of African behavioral research that actually reflects African realities.

Option 1b: Support our African-led proof of concept.

If you’d rather support work already underway, PROMISE Labs Africa is a solid choice. We are lean - just me, two brilliant full-time Research Associates (Deborah Odaudu and Kamikun Adekunle) and researchers who join us on a project-to-project basis.

We are currently conducting multiple small-scale behavioral studies to better understand how people in African communities actually navigate health-related behaviors. We’ve already got a preprint43 out for decision-making around getting a HIV vaccine44, another exploring demand for elderly care facilities45 among Nigerians, and a mixed-methods study on health insurance about to cross the finish line. Upcoming projects include studies on the recently rolled-out malaria vaccines, alternative approaches to public safety that don’t rely on traditional policing, sustainable waste management strategies, and drivers of electricity consumption decisions.

None of this work is currently backed by big institutions or massive grants. Every dollar goes directly into funding researchers, fieldwork, and data collection. No bloated overhead. No middlemen. When you donate to PROMISE Labs Africa46, you’re directly supporting real African-led research that starts with African questions, not imported assumptions.

With your support, we can grow our team of research fellows and associates, and scale our research. Donors can contribute at https://givebutter.com/9jm8ui. You can also email me at promise@promiselabs.africa to talk more about how your contribution could support specific research that interests you.

Option 2: Start your own microgrant program.

If you’re ready to dive deeper and start your own program, fair warning: it’s not for everyone, but it can be incredibly rewarding. The beautiful thing about microgrants is that you don’t need a fancy foundation letterhead or a corner office to make this happen. You can run a lean, high-impact microgrant program from your kitchen table or bed. You don’t even need to be African to fund African research effectively; what matters is respecting local expertise and letting researchers lead their own work.

Now, I’ll be honest - I don’t have a roster of people who have set up microgrant programs for African researchers to point you towards. What I do have is my experience as an African behavioral researcher, alongside insights I have picked up from independent researchers like Nadia Asparouhova474849 and Adam Mastroianni50 who have written extensively about funding research (though not Africa-focused).

If you’re serious about this, here’s a practical blueprint for getting started:

Start small and expect to learn as you go. Your first round doesn’t need to be perfect. Start with modest amounts - maybe $50-200 per project - and fund just 2-3 researchers to begin with. See what works, learn from the experience, adjust your approach and potentially scale up the amounts and number of grants.

Keep the application simple. A Google Form with a few open-ended questions (What do you want to do? Why is it important? How will you spend the funds?) is often enough. Set word limits to keep things tight and avoid fatigue on both sides. Clarity over formality, always.

Establish clear communication channels. Create a fresh email address just for the microgrant. Be crystal clear about expectations: Not everyone will get funding. Not everyone will get feedback on why they didn’t get funding. And yes, sometimes you might go quiet for a bit because you actually have a day job and a life outside of this!

Review applications in batches. Do monthly or quarterly rounds because trying to evaluate them one by one as they trickle in is the highway to burnout. Invite a few trusted friends to help if you need a second pair of eyes, but make sure they are not just available, but also aligned with your vision.

Shortlist wisely. Look for well-grounded proposals. Check the applicant’s digital footprint - their social media, any previous work, their general online presence. A quick video call can also go a long way in checking alignment and weeding out fluff.

Disburse funds directly. Use whatever platform won’t give you or the researcher a migraine. PayPal works in some places, Wise in others. Mobile money services like M-Pesa and O-Pay are very popular in countries like Kenya and Nigeria. You may also consider fintech platforms, such as Paystack, LemFi, Afriex, and Sendwave, which are fast, cheap, and purpose-built for African contexts. And yes, even cryptocurrencies can work - especially in countries with volatile currencies or restrictive banking systems. Just make sure the recipient knows how to receive and convert it safely.

Follow up lightly. You don’t need a full impact report. A one-page summary of findings is usually enough. Just something that shows the work happened and gives you a glimpse into what they learned. No dashboards. No PowerPoint slides with animated transitions. This reduces administrative burden while still offering some form of accountability. The goal is to empower these researchers, not micromanage them.

VII.

The seeds of this piece were planted on that beach in Twon-Brass, where I first started wondering why Africa was such a walking contradiction of abundance and scarcity. Years later, as a grad student, I spent countless hours poring over journal articles and started to notice a pattern: study after study conducted in WEIRD societies, with findings generalized to “human behavior” as if the rest of humanity were just footnotes.

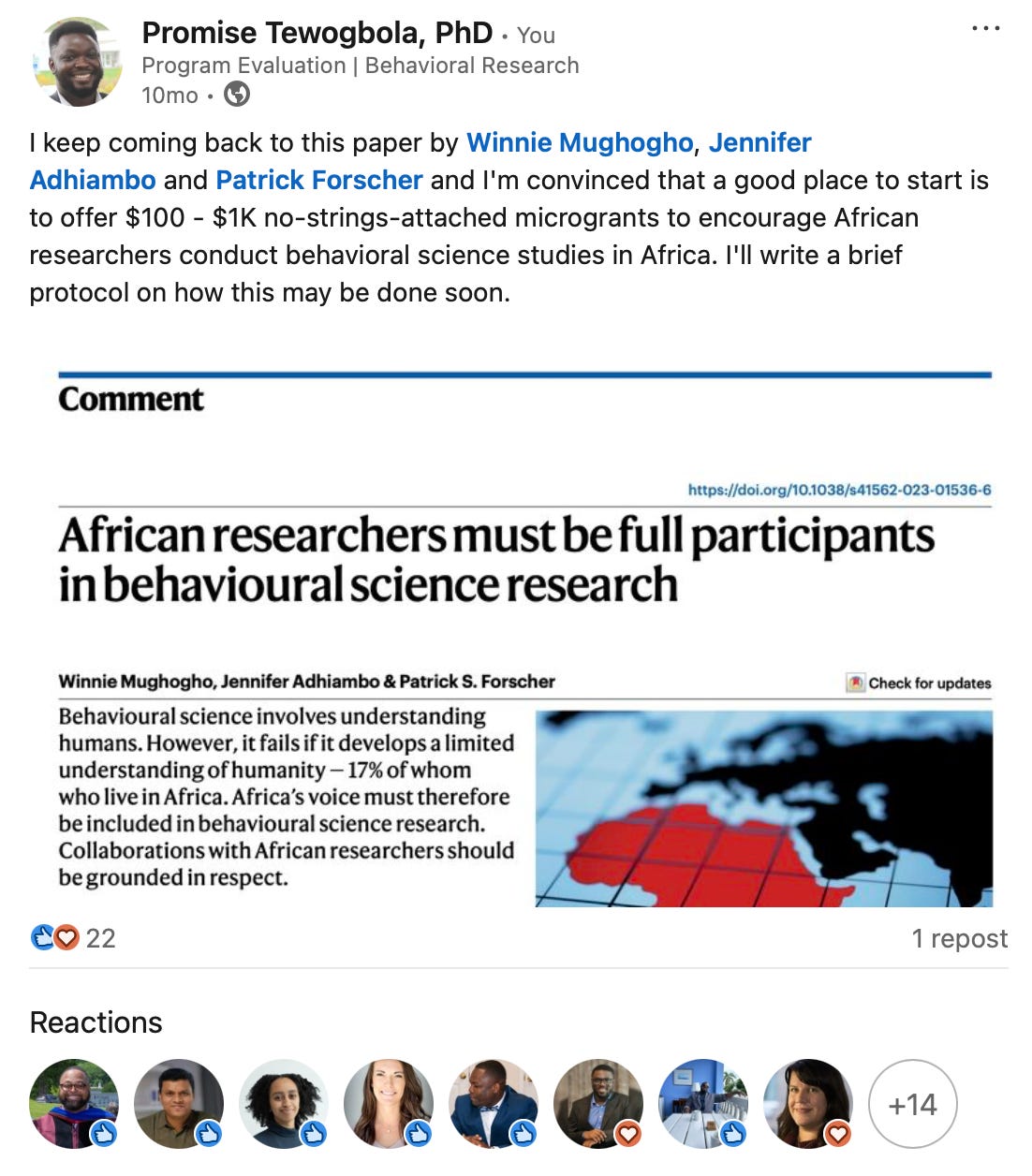

Not long after I earned my PhD in May 2024, I came across a 2023 article titled “African researchers must be full participants in behavioural science research”51 by Winnie Mughogho, Jennifer Adhiambo and Patrick Forscher. Here were African researchers powerfully putting words to what I had long felt but never quite articulated: behavioral science had systematically relegated African researchers to glorified RAs while marginalizing African voices and perspectives. The realization hit me. Thanks to the WEIRD bias baked into the field, the way Africans actually live and make decisions sat squarely in the blindspot of most attempts to understand the continent’s struggles. The solution seemed clear: we needed to put research funding directly into African hands. I fired off a LinkedIn post, publicly promising the world I would write a protocol on how microgrants could accelerate behavioral research in Africa.

This essay is that promise - finally kept! What I thought would be a quick and straightforward technical protocol somehow had other plans. Ten months, several drafts, and over four thousand words later, here we are.

Better late than never, because the conditions for change have never been better aligned. There’s a generation of brilliant African researchers who are ready to tackle the complex behavioral questions that shape life on the continent. Social media has given researchers tools to share their work without waiting for permission from academic gatekeepers. And there’s now a plethora of digital payment systems that make it easier than ever to move funds across borders instantly. Together, these forces have created an unprecedented opportunity.

An individual who bets $100 on an African researcher’s idea is directly investing in the kind of intellectual infrastructure that can shape Africa’s transformation for decades to come. And the impact doesn’t end there. We now live in a world shaped by large language models trained on vast stores of WEIRD data.5253 As the rush for new, diverse data intensifies, the behavioral research that African scholars produce could become the very datasets that reshape future AI systems. The questions that African researchers are uniquely positioned to explore could expand how we think about human behavior itself.

Imagine a future where African universities are buzzing with research projects funded by individuals like you. Where policy makers in Lagos, Nairobi, and Accra base their decisions on insights generated by researchers who live in those cities. Where the next breakthrough in understanding human behavior comes not from an institute in Boston or Berlin, but from a researcher in Botswana. That future isn’t a fantasy but a reality entirely within reach. And you can help bring it to life.

The beach in Twon-Brass is still there. So are the fishermen I met, still navigating the paradox of abundance and scarcity in their struggling community. The literature reviews are still dominated by research from WEIRD societies. And the brilliant African researchers are still waiting for their chance.

But something has changed: there is a way we can start shifting the balance. A way to put resources directly in the hands of those closest to the questions.

Here’s your invitation: Share this piece. Fund a study. Start now. Don’t overthink it.

The behavioral revolution Africa needs can start with your next decision. Will you be part of it?

Promise Tewogbola, Ph.D., is a behavioral researcher whose work leverages insights from behavioral psychology, microeconomic theory, public health and behavioral economics to better understand how people make decisions impacting their lives. He is the Founder and CEO of PROMISE Labs Africa, a scientific nonprofit dedicated to cutting-edge translational behavioral research in Africa to generate actionable, evidence-based insights that inform effective policies and drive positive outcomes for Africans.

This essay exists because many brilliant people generously shared their time, insights, and honest feedback during its evolution from scattered thoughts to the piece you just read. My deepest gratitude goes to Emily Brooke Felt, Dolores Lucero, Malarkodi Selvam, Rose, Ved Shankar, Lily Luo, Aishat Ateiza, Vidhika Bansal, Suzanne Hitcho, Yolanda Truong, Rita Koon, Celeste, Davide Bruzzone, William, and Dan Xin Huang. They helped midwife this essay through multiple iterations, challenged my assumptions, sharpened my arguments, and saved me from the pitfalls of going the lone mad scientist route. Their thoughtful engagement has transformed what could have been a rambling academic rant into something that might actually spark the conversations and actions this work desperately needs. Any remaining flaws are entirely my own.

Economists typically define rational behavior as the pursuit of choices that maximize happiness or utility, assuming people intuitively know what they want, stick to their preferences over time, and have access to all the relevant information. But in reality, humans (Africans or otherwise) rarely have perfect information, and even if we did, we neither have the time nor cognitive bandwidth to carefully deliberate on every single decision. Hence, we practice ecological rationality which relies on mental shortcuts and local cues that might seem irrelevant or irrational from the outside but make perfect sense in context. https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_2543502/component/file_2561658/content

A type of bean pudding eaten by the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moin_moin

Solidified pap made from ground corn. https://articles.connectnigeria.com/origin-of-nigerian-foods-eko/

Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission [of HIV]

A West African rice dish. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jollof_rice

Motorcycle taxi. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okada_(motorcycle_taxi)

Decision on the Report on the Conference of Ministers of Science and Technology, Doc.EX.CL/224 (VIII), bullet number 5. It’s on page 23: https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/9639-ex_cl_dec_236_-_277_viii_e.pdf

Skills for Science Systems in Africa: The Case of ‘Brain Drain’. https://suraadiq.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Skills-for-science-systems-in-Africa.pdf

Pounded yam. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pounded_yam

Roadside restaurant. https://www.oed.com/dictionary/buka_n?tl=true&tab=meaning_and_use

P.R.O.M.I.S.E is an acronym for Purposeful Research Optimizing Meaningful Interventions for Societal Enrichment

While Option 1a lets you fund independent researchers through our pilot microgrant program, Option 1b supports our in-house research efforts. Both make the same bet: that Africans are best positioned to study African behavior.